We rented richly

I don’t remember us being rich as I was growing up. Nor, however, do I remember us being poor.

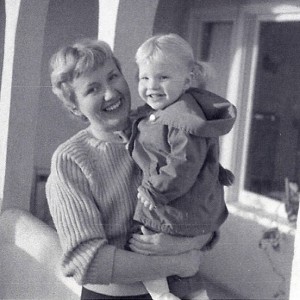

When I was born, we were living in a house a mile from the ocean in Laguna Beach. When I was one year old, we moved to a house across the street from the ocean. And, when I was five years old, we moved to a house on a cliff, directly above the ocean. When you look at it that way, I suppose we were rich.

We lived on rich land, indeed. It was land that would become even richer. Yet my father, Edmund, rented. He refused to buy.

A renter in a buyers’ market

Long before hedge funds and mortgage-backed securities were household names, long before Silicon Valley teemed with venture capitalists, Edmund had the foresight to move his young family to a place that would one day rival New York City zip codes for the priciest addresses in the country.

In what would become one of the world’s hottest real estate markets, Edmund chose not to buy property that would one day increase exponentially in value.

On being un-wealthy

Edmund, who was sent as an adolescent from his boyhood home in China first to boarding school in Korea, and then as a teen to The Hotchkiss School in Connecticut, would regale us with stories of having gone to prep school with the sons of the very wealthy. He, the son of Presbyterian missionaries to China, by comparison, was poor. And that worldview seemed to inform his thinking about having money from then on.

My memory is that for him, being without wealth was a way of staking his identity.

Heading West

His was a fascinating combination of fear and bravado. On one hand, when he was contemplating moving my mother, Helen, and my older siblings West, from Ossining, New York, to Laguna Beach, he wrote of his fear of making the wrong choice, financially-speaking. Later, as fervently as he had promised Helen a new start in Laguna Beach, he justified why it had not worked out the way he had promised.

Adrift in a sea of new-age wealth

It’s ironic, and not quite surprising, that Edmund never did buy property in Laguna Beach. Ironic, because he had turned his back on wealth, yet he had planted his family in the epicenter of it. Not quite surprising, because to him, having no wealth, in a sea of wealth, seemed to suit him just fine.

Edmund died relatively young, and poor. I’m not sure he would have had it any other way.