A short while ago, I shared the three great books that I was currently reading–and thoroughly enjoying, with a promise to post about each.

I shared here a wonderful book that touches on shame and vulnerability, Daring Greatly by Brené Brown, and here a fabulous book on getting to know and love fear, Nerve, by Taylor Clark.

In this post, I’ll share some of the wonderful take-aways from the third of the three, If Only: How to Turn Regret into Opportunity by Neal Roese, Ph.D., a leading researcher in the field of regret.

Although I can’t begin here to capture the breadth of research that the author covers in this excellent book, I can tell you that he sheds a fabulous light on the marvel and miracle that are our brains.

With wit and humor, and a fair share of wonder and awe, he talks about our “psychological immune system,” and other ways in which our brains and our minds work together to keep us in one piece.

One of the ways our brain helps us attempt to make sense of an often senseless-seeming world is through what science calls, counterfactuals.

Simply put, counterfactuals are fictional narratives of what might have happened if things had gone differently than they actually had. There are two types of counterfactuals, and they make us either feel better, or worse.

Downward counterfactuals lift our spirits because they tell us that it could have been much worse. Say, for instance, we were almost in a major traffic accident, but narrowly avoided it, with only a small dent. There is a momentary sense of euphoria, when we realize how bad things might have been (the small dent notwithstanding), but weren’t.

Upward counterfactuals on the other hand, are more difficult to handle emotionally, because they tell us how much better things might have been, if we had only taken a different course of action. The value in these, Dr. Roese helps us to see, is that they serve as compasses, so to speak, giving us direction for future actions.

A life lived without hope is a life almost unbearably difficult to live. If we’ve made mistakes, hope tells us that tomorrow may very well be better.

It is in this setting that regret plays such a fundamental role. As Dr. Roese says so eloquently on the closing page: “Regret is good. Thinking about what might have been is a normal component of the brain’s attempt to make sense of the world, and of the human quest for betterment.”

And the quest for betterment is a wellspring of hope.

“You’re not alone.”

How many of us have heard those words and felt an instant wave of relief? To know that others have shared our fear, our embarrassment, our quandary, is to know that we are okay.

And, to know that we are okay is to know that we belong. To know that we belong is, of course, fundamental to our human experience.

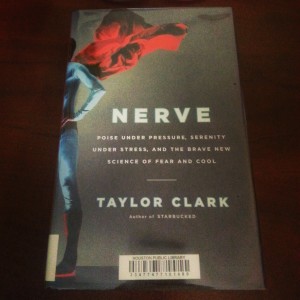

Taylor Clark’s excellent book, Nerve: Poise Under Pressure, Serenity Under Stress, and the Brave New Science of Fear and Cool, was one big, “you’re not alone” message of assurance for me.

Through an engaging presentation of real-life examples of famous individuals who have felt and faced their fear, and interviews with noted fear authorities, Clark introduces the reader to the technical aspects of fear, shows us where fear lives in the brain (Hello, Amygdala!), and provides Calls to Action for surviving the often debilitating effects of fear.

For anyone who has ever struggled with fear–whether fear of heights or fear of an audience–and this includes all of us (to be human is to fear), it will come as a welcome relief to know that fear can not only be our friend, it can be our savior, warning us of dangers and directing us to alternative courses of action.

Perhaps one of the most exciting take-aways from Nerve for me was to learn that one of the surest ways to calm our fears is to expose ourselves as much as possible to the very thing we fear.

By doing so, we are in a sense de-conditioning that part of our brain responsible for the fear reaction, letting it know that although we appreciate its valiant vigilance, it is no longer needed in that particular situation.

Once we let our fear rear-guard know that we’ve got a situation handled, the rational, thinking part of our brain can resume its starring role.

And the thinking part is where so much of the stuff that makes life worth living resides.

I have thoroughly appreciated having my pre-conceptions regarding fear turned on their head, as I’ve devoured the painstaking research and skillful writing that author Taylor Clark (Starbucked) has brought to the subject in his aptly titled book, Nerve.

I’ll share some thoughts on Nerve in my upcoming post.

This California girl, who confesses to longing to click her heels on her beloved New York City sidewalks, has come to appreciate the vitality and versatility of her adopted city, Houston.

Continue reading Oh, the Wonderful Sights You’ll See in Houston!

Many of my friends and contemporaries today are caring for their parents, or worrying about having someone else care for their parents, or worrying about how they will pay for someone else to care for their parents.

As fate would have it, these are concerns I do not share.

My entire adult life has passed without my mother, who died when I was a teenager, and more than half of my adult life has passed since my father died.

In their absence, time has smoothed the rough edges of their faults and perhaps exaggerated the merits of their strengths.

I have spent more time missing them, and wishing they were part of my life, than I have in resentment toward my father for the very human mistakes he made.

A few posts ago, I shared the books adorning my bedside table. Included in that enriching stack was Daring Greatly by celebrated author and University of Houston researcher, Brené Brown.

It’s an incredibly rich read, and here is the larger message I’ve so far gathered from Daring Greatly:

To live fully, we need to be willing to be vulnerable;

To be vulnerable, we need to be willing to put ourselves out there;

To put ourselves out there, we need to know that we are enough;

To know that we are enough, we need to be resilient against the siren call of shame (that tries to convince us that we are not enough);

To not buckle to the siren call of shame, we need to be willing to cultivate “shame resilience;”

To develop shame resilience in order to be vulnerable, we need to be willing to practice “daring greatly” daily/hourly; and,

To be willing to keep practicing, we need to realize that only by being vulnerable are we truly connected, and hence, truly alive.

As an attorney practicing U.S. immigration law in 1990s New York City–in the aftermath of the fall of the Soviet Union–I joined my colleagues in compiling compelling applications on behalf of former Soviet citizens seeking new, often humble lives in America.

That was back when the abandoned coliseum still occupied its western hold on Columbus Circle.

What a difference twenty years make.

Continue reading A Different Kind of Russian in a Different Kind of NYC

This has been a week of incredible revelations and seeming obfuscations over at NBC Nightly News, and of delighted daggers of wit over at Twitter.

On Wednesday, news emerged that the anchor of NBC Nightly News, Brian Williams, had exaggerated, for years, the extent to which his life was put at risk during a helicopter flight in the Iraqi desert in 2003.

By Thursday, Mr. Williams had delivered an apology-of sorts, acknowledging the untruthfulness of his claims of a harrowing experience, yet wrapping his mea culpa in an ill-fitting suit of self-justifications.

Whereas he and his crew had indeed been aboard a Chinook helicopter on the heels of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, his copter did not sustain enemy fire, nor was it forced to land because of a hit by a rocket-propelled grenade, as Mr. Williams contended as recently as one week ago.

Here, then, was a man, fresh from signing a $10 million per year, 5-year contract to read and write the evening news, who apparently had been for at least ten years experiencing a sense of “not enough.”

Here was a man who looked to have all anyone could ever want–and more, yet felt a less-than so huge that he had to fabricate a better-than, a braver-than, a more-extraordinary-than too big for any single human to contain.

If it weren’t so tragic, it would be comedic. Given enough time, it may very well be.