More Designer, Less Worrier, please

It’s fascinating to realize how much of our–or, should I say, my time–is lived in the future, or to be more specific, in worrying about the future. A future that may or may not arrive.

Take, for instance, my breathless search for a new pair of glasses at the very cool, very chic online designer-glasses outlet, Warby Parker.

I am in love with almost every pair of glasses on the site. Yet, what if they look vastly different on me than they look on the site?

Yes, You Can Try Them On At Home

Not to worry. And, what a novel idea: via the Warby Parker website, I can order up to five pairs of glasses to be sent to me, so that I can try them on. At home. In front of my own mirror. All at no cost, so long as I return them.

How cool is that?

But How Will I Decide?

Even as I am excitedly clicking my way through various angles of online images though, I am simultaneously wondering how I will make a decision once the glasses arrive. After all, I might like two pairs equally well.

I am also wondering if the prescription I received from my eye doctor will need to be modified; since she’s an M.D., she wrote the prescription in a manner different from the standard optometrist’s measurements. Will I need to call her office?

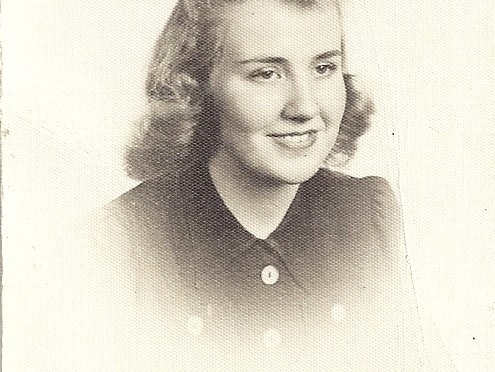

And, what if one of the pairs I like will be too much like the pair of a person whose glasses I would not like mine to look too much like?

All this worry, and I haven’t yet picked the five I’d like to try on. At home. In front of my own mirror.

But Will the Warby Parker Box Fit in My Post Office Box?

Once I choose the five I’d like to try on, I may begin worrying about which day the glasses will arrive at my post office box, whether I’ll be able to make it to my post office box on the day they arrive, and whether they’ll come in a box that will fit in my post office box.

In the meantime, I need to get back to worrying about choosing the five I’d like to try on.